|

Roll Overs:

1

2

3

|

|

|

Copyright (c) As noted in Contributor Info below.

|

14.25 grams. Iron, IIIAB

TKW 2550 kg. Fall not observed. Found 1863 in Saudi Arabia.

Steve writes:

Recently, Anne Black posted a very nice slice of the Wabar meteorite. While my slice is considerably smaller and much less impressive, I wanted to post it anyway so as to have an opportunity to detail the meteorite's interesting history.

Wabar meteorites and impactites are found scattered around three roughly circular craters in Saudi Arabia's Empty Quarter (Rub' al Khali in Arabic) – a huge desert in southern Saudi Arabia which, due to its enormous dune fields with no fixed landmarks and temperatures that often exceed 130° F, is considered to be one of the most remote places on Earth.

The Quran describes a city – Iram of the Pillars – within the Empty Quarter that had been destroyed by fires from heaven because of the wickedness of its king (there are several other names associated with this lost city, including Ubar and Wabar). Since tribespeople called the place al-Hadida – meaning "a piece of iron" in Arabic – English explorer Harry St. John Philby presumed he could find potentially valuable iron artifacts there. So in 1932, despite local Bedouins' warnings that "where there is no water, that is the Empty Quarter; no man goes thither", Philby decided to search the area for this mythical city.

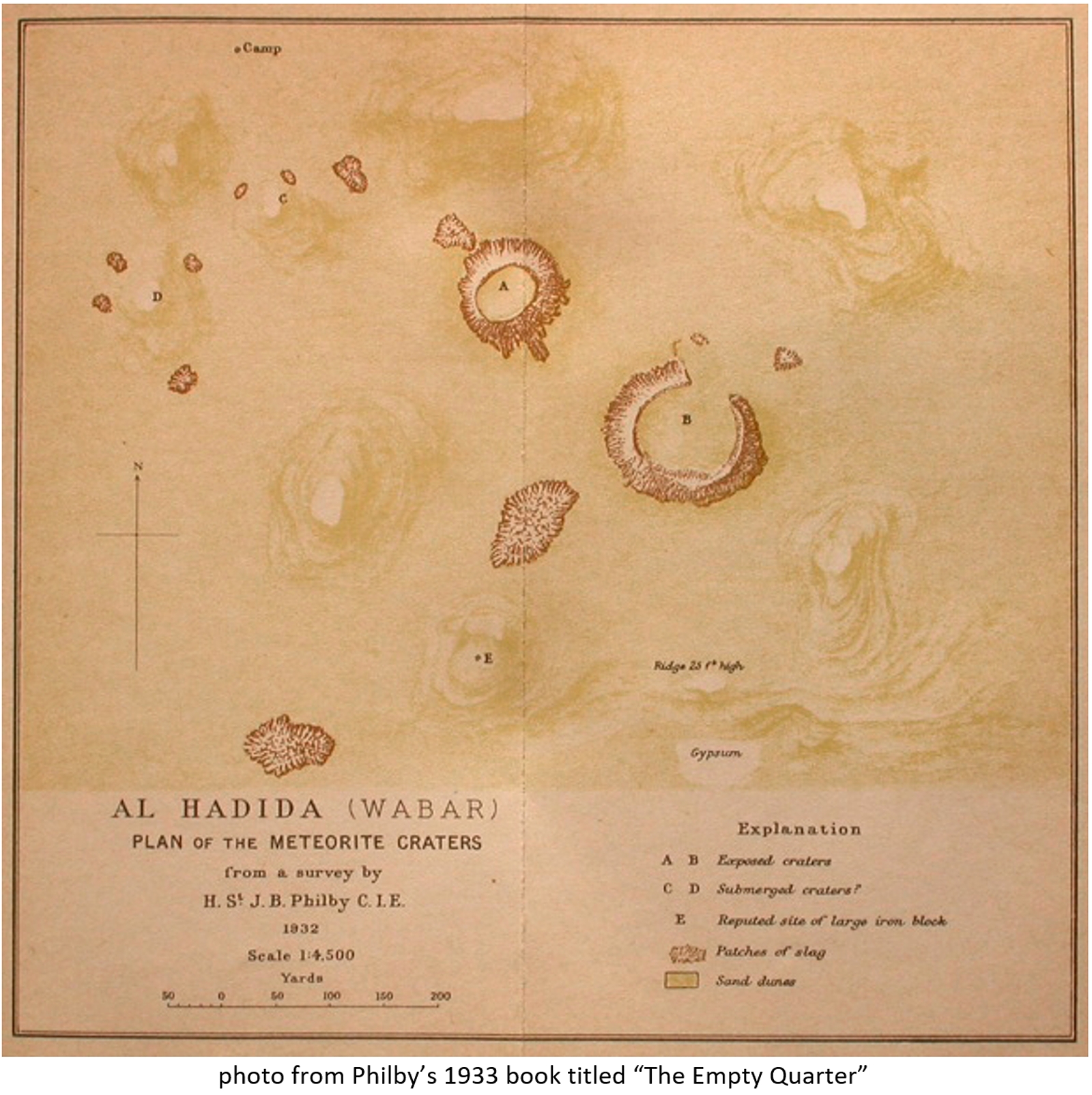

In 1933, a month into his third journey, Philby found two large circular depressions – one 116 meters in diameter, and the other 64 meters – that were partially filled with sand (see Photo 1 for Philby's map of his finds). Surrounding these craters were metal fragments and dark glass of of various shapes. Because there are no natural iron deposits in that area, Philby sent a piece of the metal he'd found there to Dr. L. J. Spencer of the British Museum, whose analysis produced results consistent with meteorites: 90% iron and 5% nickel, with the remaining material consisting of various elements that included copper, cobalt, and an unusually high concentration of iridium, the latter in particular suggesting that the area Philby found was a meteorite impact site. Almost three decades later, the discovery of coesite in the glass would further support that theory (coesite is a shocked form of quartz known to be a product of meteorite strikes).

[While the impactite comes in a variety of shapes, the Bedouins thought the glassy spherical ones were pearls – hence the name "Wabar pearls". Scattered all over the area, wind-sorting resulted in these "pearls" decreasing in size with distance from the craters. The glass is about 90% local sand and 10% meteoritic iron and nickel, the latter giving them their black appearance.]

Many pieces of the meteorite have been found in the years after Philby's travels, and they've been named after the city of Philby's quest. The largest – recovered in 1965 and weighing 2.2 tons – was christened "the Camel's Hump" and was initially on display at the King Saud University in Riyadh before it became the entry piece for the new National Museum of Saudi Arabia in Riyadh. But it wasn't until May of 1994, when U.S. Geological Survey scientist Jeffrey C. Wynn was invited to join an expedition to the site Philby had found over six decades earlier, was a third 11-meter-wide crater discovered – a crater that like the others was now almost completely filled with sand.

The valley containing these craters is named Najd, which is sometimes spelled Nejd. So in 1863 – long before Philby's discovery of the meteorites – when two initial masses were found, they were given the name Nejed, which is the European spelling of Nejd (one of several synonyms listed in the MetBul under the Wabar entry).

These two masses were similar in size, with one weighing 131 pounds and the other 136. The former – a roughly triangular piece measuring about fourteen by eleven by nine inches – was brought to Europe in 1885 by a Persian agent who sold it to the British Museum, where it has since been on display. Included with the meteorite was a letter from his Excellency Hajee Ahmed Khanee Sarteep (Sarteep was the Grand Vizier of Muscat, having previously been the Governor General of Bunder Abbas in the Persian Gulf). The letter included the Persian date of 14th Di Koodah, 1301, A.H. (1883 A.D.) and said:

In the year 1282, after the death of Mahomed, when Maime Faisole Ben Saoode was Governor and General-Commander-in Chief of the Pilgrims, residing in a valley called Yakki, which is situated in Nagede (Nejed) in Central Arabia, Schiek Kolaph Ben Essah, who then resided in the above named valley, came to Bushire, Persian Gulf, and brought a large thunderbolt with him for me, and gave me the undermentioned particulars concerning it.

In the spring of the year 1280, in the valley called Wadee Banee Kholed in Nagede, there occurred a great storm, with thunder and lightning; and during the storm an enormous thunderbolt fell from the heavens accompanied by a dazzling light, similar to a large shooting star, and it sank deep into the earth. During its fall the noise of its descent was terrific. I, Schiek Kolaph Ben Essah, procured possession of it and brought it to you, it being the largest that ever fell in the district of Nagede. These thunderbolts, as a rule, only weigh two or three pounds, and fall from time to time during tropical storms.

The above concludes the narrative of Schiek Kolaph Ben Essah. The said Schiek, who brought me this thunderbolt, is still alive and under Turkish Government control at Ioodydah near Jeddah. I myself saw in Africa, four years after the above date, a similar one, weighing about 135 pounds, which Schiek Kolaph Ben Essah brought to me.

The Sultan of Zanzibar, Sayde Mazede, obtained possession of it and sent it to Europe, for the purpose of having it converted into weapons, as when melted and made into weapons they were of the most superior kind and temper. For this reason I have forwarded my thunderbolt to London, considering it one of the wonders of the world, and may be a benefit to science.

But the meteorite said to be fashioned into weapons was, unbeknownst to Mazede, instead brought to the British Museum in hopes of a sale; while the museum was not interested, its director sent it to James R. Gregory – a famous meteorite enthusiast who immediately purchased the piece for his collection. After Gregory's passing, Henry A. Ward obtained it, where it became part of the Ward-Coonley Collection of Meteorites later displayed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Despite this subterfuge, the Sultan of Zanzibar did eventually receive his weapons, though obviously they were not made from his meteorite. In fact, while some meteorites are more workable than others, Nejed was described as having metal grains too short to forge into a durable cutting edge, which obviously is counter to the “superiority” of the weapons described by the Sultan and more consistent with his agent having had other metal used in their manufacture after pocketing the proceeds of the meteorite's sale.

There is considerable question regarding the actual date of the meteorite's fall. The craters have become nearly full of sand since Philby's discovery, which at that time were reported as being only partially filled – a fill rate that suggests a more recent fall (searching for “Wabar Crater” in Google Maps results in some great images of the sand-filled craters and surrounding areas that were taken in 2021). And thermoluminescence dating in 2004 indicated the impact site was no more than 290 ± 38 years old, consistent with Arabic reports of a southeast-traveling fireball having passed over Riyadh in 1863 or 1891, the former being coincident with the original two Nejed finds (and the same as the 1280 A.H. date in Sarteep's letter). Conversely, fission-track analysis of glass fragments suggests the meteorite's impact took place thousands of years ago. To reconcile this inconsistency, some have proposed that Nejed may be a separate fall from that which created the Wabar impactite, but analyses of both the Nejed and the more recent Wabar meteorite finds show them to be compositionally identical, and the impactite's proximity to the likely sub-300 year-old craters suggests a relationship that their fission-track analyses contradict.

The particular crusted part-slice in this post purportedly came from Texas Christian University's Monnig Meteorite Collection via Marlin Cilz of Montana Meteorite Labs, who acquired it several years ago and more recently sold it to the dealer we purchased it from (Photo 2 shows it in the Riker box with the label we received with it). The crusted edge was badly oxidized, so the original museum inventory label on the unetched side (Photo 3) was carefully removed, the meteorite stabilized, and the label reattached in its prior location.

Photo 1 copyright Harry St. John Philby

Photos 2 and 3 copyright Steve Brittenham |

Found at the arrow (green or red) on the map below

|

|

| |

Steve Brittenham

8/19/2023 10:14:58 PM |

Thanks, all, for the kind words. And thanks, Anne, for the reference. |

Graham MacLeod

8/19/2023 5:38:44 PM |

Great research Steve,

The history behind this meteorite is well documented and the piece you show is great.

Thanks M8

Cheer's |

Anne Black

8/19/2023 1:23:34 PM |

Thank you Steve, I am glad you liked that slice of Wabar. And yes Wabar is very interesting, meteorically, geologically, and historically. If you want to know more about the mysterious city of Ubar destroyed in a instant by some divine intervention, I recommend the book "The Road to Ubar" by Nicholas Clapp. And yes the city existed, and it has been found. It was indeed destroyed abruptly, but no divine intervention needed. |

John lutzon

8/19/2023 12:55:54 PM |

Thank you for your time, research and write-up. Well done. Oh yeah, nice Nejed. |

matthias

8/19/2023 8:26:29 AM |

Great write-up regarding a great iron. |

Vincent Stelluti

8/19/2023 5:53:57 AM |

Fantastic story, thank you |

Alexander Natale

8/19/2023 5:31:21 AM |

Great informative post, Thank You very much for sharing. I really enjoy reading the stories about famous Meteorites. |

| |

|